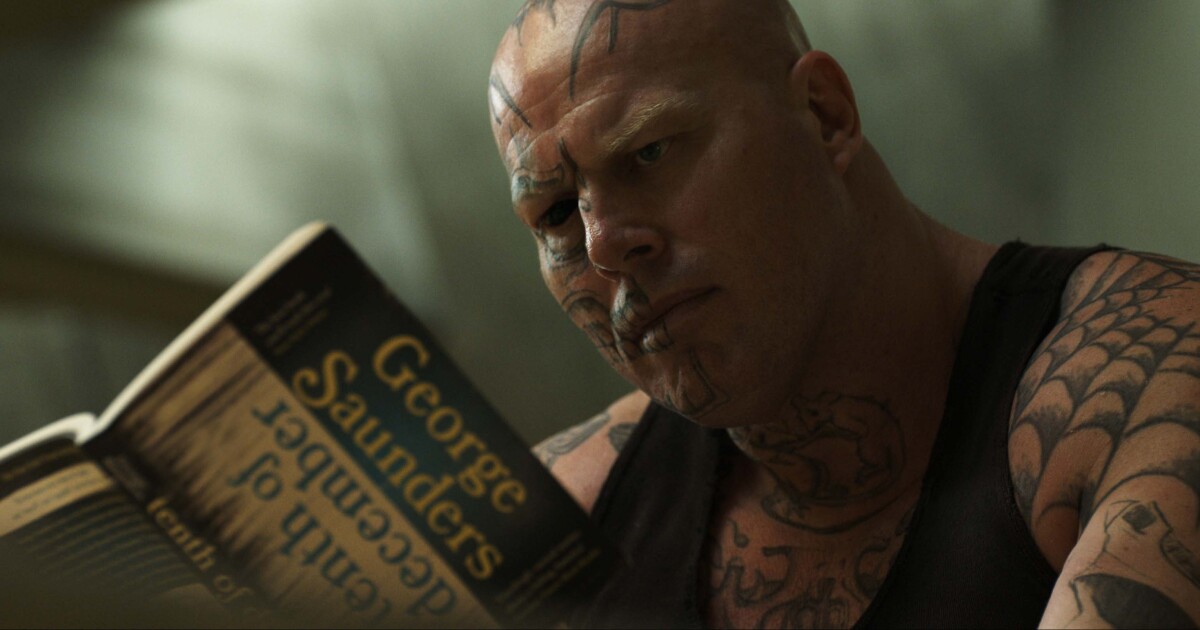

George Saunders’ “Escape From Spiderhead” is the stuff of nightmares, or at least of mine: torture, mind control, lifelong regret. Published in the New Yorker in 2010 and collected in Saunders’ “Tenth of December” in 2013, the short story puts me in mind of art-house films by miserabilists like Gaspar Noé and Lars von Trier. But in greenlighting the adaptation, Hollywood had other ideas.

Which is reasonable enough: Many of Saunders’ stories have unexploited potential for Hollywood studio films. Bard of conflicted white guys and dispenser of folksy wisdom, Saunders has made a career of old-fashioned morality tales green-screened with photogenically fantastical inventions. His stories are full of Everymen-turned-moral heroes — or moral failures, no less instructive. They’re lessons on how to do what’s right, of the kind John Gardner famously demanded from fiction. “Escape From Spiderhead” fits that mold, with a redemption arc that could map neatly onto a star-studded dramedy.

George Saunders accepting the 2017 Man Booker Award for his novel “Lincoln in the Bardo.”

(Chris Jackson / Associated Press)

Yet in “Spiderhead,” the adaptation by Joseph Kosinski (“Top Gun: Maverick”) that opens this week, Saunders’ work is little more than a prop. The film’s writers, Paul Wernick and Rhett Reese (“Deadpool”), fundamentally misconstrue Saunders’ story. Where “Escape From Spiderhead” posed penetrating questions about complicity and sacrifice, “Spiderhead” ignores them in favor of flashy fisticuffs between black hats and white. Escape no longer happens through self-transcendence; instead, it’s by seaplanes and speedboats.

In Saunders’ story, narrator Jeff is serving time at a New York state prison nicknamed “Spiderhead.” Spiderhead lets incarcerated people participate in pharmaceutical trials in exchange for a separate and ostensibly easier confinement. The drugs’ intended psychoactive effects range from trivial to life-changing. Researcher Abnesti and his assistant administer them through an insulin pump-type device, observing in a control room, and submit data to the manufacturer, as do colleagues elsewhere. Despite a charade of consent, subjects are aware that if they refuse to cooperate, the experimenters can fax Albany for permission to use an obedience drug. Jeff would also risk his cherished calls with his mom. His only other activity is attending therapy.

Saunders’ Abnesti was a suburban dad and mid-level cog, evil’s banality personified. The film makes him into Dr. Strangelove meets Elon Musk, an erratic pharma bro entrepreneur. This Abnesti gets high on his own supply, shadowboxes in his on-site suite and conceals damaging information: calendars, news, test results, his agenda. Now he’s flat-out sadistic, tormenting residents for no apparent clinical reason.

Chris Hemsworth is convincing as Abnesti the out-of-control biohacker. Yet in resorting to the cliché of a solitary mad scientist, the writers miss something crucial to Saunders’ message: that corrupt institutions rely on compliance from many regular people. Saunders’ stories often urge conscientious resistance. “Escape From Spiderhead” builds on motifs he developed in other stories, like corporate involvement in law enforcement (“My Flamboyant Grandson”) and medicated captive research subjects (“Jon”). Some of his protagonists must respond to methodical violence by joining in or paying a price (“Ghoul,” “Elliott Spencer”). By personalizing the story’s threat in Abnesti, the writers remove the existential dilemma on which Saunders hung his plot.

Chris Hemsworth as Abnesti in “Spiderhead.”

(Netflix)

The incarcerated Jeff (Miles Teller) has to rescue a woman; in the story she’s a near-stranger, Rachel; in the movie she’s a newly minted love interest, Lizzy (Jurnee Smollett). The film softens Jeff and Rachel’s violent crimes into Jeff and Lizzy’s acts of negligence — which conveniently tidies up any moral gray zone regarding their imprisonment. While Saunders’ narrative hinges on Jeff’s altruism toward a repeat recidivist he’s indifferent about, the film relies on his attachment to a romantic partner. Moreover, where the story’s climax tests Jeff’s compassion, the movie’s climax tests his butt-kicking skills.

Sparing Jeff the tough choices, the writers shunt moral transformation onto a minor character. Finally, Abnesti’s ending sequence is stylish but empty; he’s essentially a supervillain. It’s much easier to eliminate a lone evil genius than to overhaul a dangerous system.

The writers needn’t have denatured the story so radically to make it an action film. Saunders’ original has meaningful plot elements in common with Rian Johnson’s future-set “Looper” and Susanne Bier’s war movie “Brothers” (the latter remade by Jim Sheridan). Both films stick to the ribs precisely because they face their protagonists’ conundrums.

Looking for visual thrills, Kosinski wastes the enormous cinematic potential of both of the story’s important drugs: a love potion and Darkenfloxx™. We experience neither the vivid reveries nor the Darkenfloxx-induced horrors Saunders describes, merely observing reactions instead. One can only dream of what a surrealist like David Lynch or Josephine Decker would have done with the scenes.

A couple of new, auxiliary drugs feel true to the story, and the original bits of the score are effective. But Kosinski leans heavily on a handful of glam, New Wave and soft-rock songs to signify — what, exactly? A nod to Dr. Frank N. Furter, Abnesti as ironic hipster, stimulus-progression Muzak? It’s unclear, but neither the playlist nor the “Miami Vice”-meets-Bauhaus design aesthetic substitute for actual substance.

Saunders’ story has firm roots in reality. Incarcerated people can sometimes jeopardize themselves physically in exchange for leniency. Prison wildfire crews, for example, can be eligible for early release and even expungement. Since the 1970s, though, safeguards have nearly excluded incarcerated people from pharmaceutical trials. Over the years, some have sued for their right to participate. The issue came up again during COVID vaccine trails, with prison populations especially vulnerable to the pandemic. In another sense though, the prison-industrial complex is a constant human experiment: How young can we lock people up? How long can we isolate them? What are suitable methods of execution? Often, the way our justice system answers these questions is harsher than the utilitarian logic of Saunders’ Abnesti and company.

Yet rather than abide in the author’s eerily pedestrian near-reality, the film undermines any verisimilitude with a fanciful vision of prison. In press notes, Kosinski cites what he sees as his film’s present-day plausibility. After watching it, though, I doubt the onetime architect has ever set foot inside a corrections facility. On one hand, residents of his Spiderhead don’t even have clerestory windows. On the other, they have unsupervised access to knives (never mind belts, glass vessels, underwire bras, etc.; this Spiderhead is crawling with contraband).

Saunders’ successful absurdist satires balance recognizable characters with off-kilter scenarios. The author adapted his own story “Sea Oak” for a 2017 pilot with Glenn Close (on Amazon, a Saunders-esque dystopian entity if ever there were one). The show didn’t go to series, but it hints at how Saunders might bring his work to the screen: Even in a world where the heroine becomes a telekinetic zombie, the milieu is mundane, the delivery deadpan.

“Escape From Spiderhead” is one of Saunders’ most horrific tales, but its run-of-the-mill bureaucracy invites reader identification. Little in the film feels so quotidian. The over-the-top qualities of Abnesti, his compound and the film’s third act counter Saunders’ Beckettian portrayal of a hell uncomfortably close at hand.

Several months after publishing “Escape From Spiderhead,” Saunders instructed students in a graduation speech: “Do those things that incline you toward the big questions, and avoid the things that would reduce you and make you trivial.” Too bad “Spiderhead” didn’t take his advice.

Johnson’s work has appeared in the Guardian, the New York Times, Los Angeles Review of Books, the Believer and elsewhere. She lives in Los Angeles.